"Good" practice for water management and pollution prevention during construction

- Poppy Grange

- Aug 19, 2024

- 7 min read

Effective water management and pollution prevention are critical challenges faced by construction projects, especially within the UK's regulatory framework. In previous insights, we explored the legal obligations associated with water management and pollution control, highlighting the significant risks to projects when these areas are neglected. However, these risks also present opportunities to enhance environmental stewardship, ensure compliance, and protect both the project and the surrounding environment.

In this article, we delve into some practical strategies for achieving "good" water management practices during construction, tailored to the unique conditions of each site, discussing the importance of planning, modelling, and the judicious use of chemical treatments.

Understanding "good" in water management during construction

In the environmental sector, we are often quick to highlight bad practices and caution against what shouldn't be done, yet we rarely celebrate or define what "good" actually looks like. Perhaps this is because we're hesitant to reveal too much, or we simply assume that everyone already knows what constitutes "good" practice.

While the concept of "good" is, of course, subjective, the current situation has muddied the waters (pun intended) even further. In England, the Environment Agency (EA) has withdrawn its Guidelines for Pollution Prevention (GPPs) for legal reasons rather than any technical shortcomings. Meanwhile, organisations like SEPA (Scotland), Natural Resources Wales, and the Northern Ireland Environment Agency continue to support Pollution Prevention Guidelines (PPGs) which are available on NetRegs.

Regardless, whether it's GPPs or PPGs, all agencies refer to CIRIA guidance as the standard for designing pollution prevention and water management strategies. This is what regulators will expect to see in the event of an incident, so it should be our focus.

Key takeaway: Focus on understanding and implementing the standards outlined in CIRIA documentation, as this is what regulators expect to see in your pollution prevention and water management strategies.

Tailoring water management strategies on construction sites

There's no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to water management during construction and silver bullets don’t exist. Each site presents unique topographical, climatic, and pollution risks, and it's essential to remember that every mitigation strategy comes with a cost.

Modelling: the first step

The initial step in any water management plan should involve modelling surface flow, as outlined in CIRIA documentation. Although the CIRIA guidance is somewhat dated, and modelling techniques have advanced, surface flow modelling remains a critical process. It helps predict how water will behave on-site during specific storm events, providing valuable insights for planning.

As with all modelling, the results are produced by the parameters we decide on, and so it’s useful to be aware of which parameters are being used to create the model - client requirements can differ from industry standard, so it’s important to understand the potential implications.

Additionally, all systems are designed to a standard which nature may or may not respect. Good design should always consider what happens when a design standard is exceeded to ensure there is not a catastrophic failure of the system.

Key takeaway: Begin your water management plan with detailed surface flow modelling to accurately predict water behaviour on-site and guide your strategy.

Suspended solids

Once the volume of surface water generated during a storm is modelled, this data can be used to determine the required size of your treatment ponds. This calculation relies on Stoke’s Law, which considers the settlement velocity of sediment particles (how quickly they sink) and the retention time (how long water remains in the treatment pond/system). As a result, where sediment pollution is involved, area, rather than volume is the deciding factor.

And when it comes to clays, the area required can be extreme. The discharge from a six-inch pump from an excavation in a clay sub soil requires 10.61 hectares of area to allow the water to be clean enough to discharge. The image below is one example to demonstrate the scale:

Key takeaway: Use the data from surface flow modelling to design treatment ponds that effectively manage suspended solids based on settlement velocity and retention time.

Why relying on permanent SuDS during construction is a bad idea

Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) are designed primarily to manage flood risk after a project is completed by retaining water and reducing downstream flooding. However, they are not suitable for managing water during the construction phase. Efficient treatment systems during construction should be shallow, allowing sediment to settle quickly. In contrast, SuDS are often deep and designed to hold water, making them unsuitable for the high volumes of water typical during construction. Additionally, a SuDS system is generally sized for the finished project, not for the exposed and active construction site, meaning it can easily become overloaded.

Key takeaway: SuDS systems are designed for completed projects, not active construction sites. Avoid relying on them during construction to prevent overload and inefficiency.

Space constraints: Land area is expensive and often unavailable

When you undertake the modelling recommended by CIRIA, you may find that your site lacks the necessary area to treat the volumes of water generated during rain events. Here are some strategies to reduce the area required:

Ensure you’re only managing the water you must by diverting offsite or upslope surface flow away from your working area.

Store all hazardous materials in a way that prevents their volumes from increasing due to rainfall, and ensure they are adequately contained in case of a spill.

If you can, break up your site into smaller areas. While the total area needed for water management remains the same, handling smaller volumes at multiple discharge points is often more efficient than concentrating all surface flow in one location.

Nature is your friend: Only strip the land that you need to and reinstate areas as soon as possible. By doing so, you reduce the amount of water that needs to be managed.

Key takeaway: Optimise your available space by diverting unnecessary surface flow, compartmentalising your site, and minimising land disturbance to reduce the area needed for water management.

Chemical Treatment: A necessary measure at times

When space is limited and traditional methods fall short, chemical treatments can effectively manage suspended solids, but they must be used in conjunction with proper settlement systems and in a controlled manner.

Using chemicals to manage suspended solids – it really is this simple

Flocculants and coagulants can be used to bind sediment particles together, increasing their weight and settlement velocity. According to Stoke’s Law, this allows sediments to settle faster, reducing the required area for effective water treatment before discharge. However, even chemically treated water should pass through a treatment lagoon to ensure solids settle properly. If the coagulated sediments remain in turbulent water, they could still be carried downstream or even disentangle, leading to potential environmental contamination.

As a side note, using chemicals to treat pollution on-site prior to discharging it to the water environment is a sensitive subject, the regulators will want to see that you have exhausted all the alternatives before consenting to their use. But as detailed, if there is no alternative then there is no alternative.

Key takeaway: Flocculants and coagulants can enhance sediment settling, reducing the area needed for water treatment. Ensure treated water passes through a settlement lagoon to prevent downstream contamination.

Dealing with other pollutants

Some pollutants require specific chemical treatments, such as pH adjustment which can be treated using several techniques. For particularly hazardous substances, it's advisable to seek specialist assistance or arrange for the water to be transported to a licensed treatment facility.

Key takeaway: Some pollutants require specific chemical treatments; for particularly hazardous substances, consult specialists or transport the water to a licensed treatment facility.

Silt fencing: A last line of defence

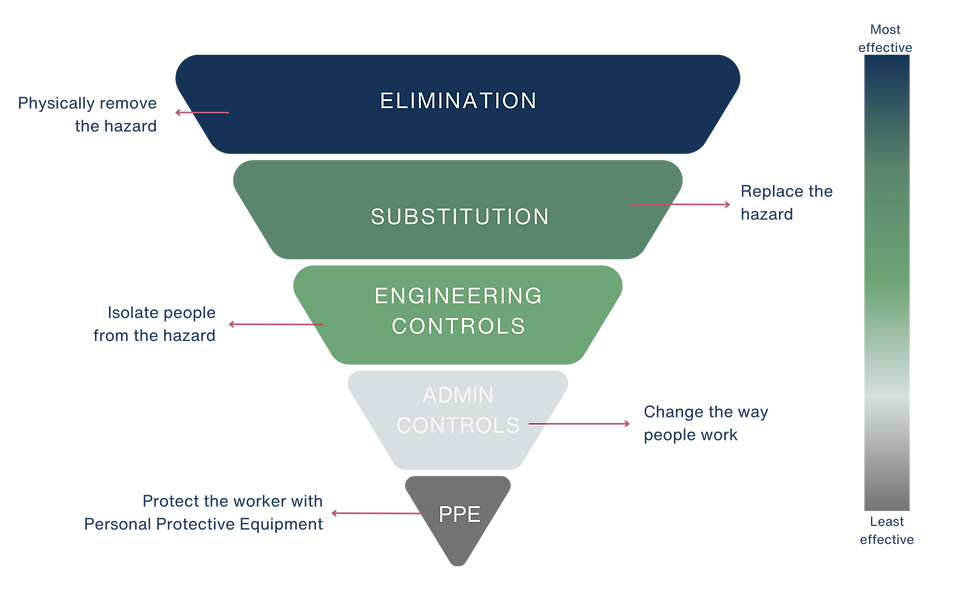

You may have noticed that we haven’t mentioned silt fencing or hay bales, and that’s intentional. These measures are akin to Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) in the context of water management. From and environmental perspective, with regards to the Health and Safety mitigation hierarchy, it's important to understand that silt fencing falls into the PPE category as shown here.

While silt fencing can provide a final layer of protection, it should not be relied upon as the primary solution to ensure your project’s compliance with environmental regulations. Instead, it should be seen as a supplementary measure, with more robust strategies taking precedence.

Key takeaway: Treat silt fencing as a supplementary measure, not a primary solution. Use it as part of a broader, more robust water management strategy.

Planning for water management and pollution prevention in the UK

In the UK, rain is an inevitable reality, and with stringent legislation in place to protect our water environment, effective water management and pollution prevention are essential. These efforts cost both time and resource.

If you opt not to use chemical treatment for managing suspended solids, you'll likely need to allocate a substantial portion of your development area—ideally on flat ground—for constructing treatment ponds. On the other hand, if chemical treatment is necessary, you must budget for the cost of acquiring the necessary products, implementing a delivery method, and establishing control measures.

Regardless of the method chosen, it’s crucial to allocate appropriate funds for a robust monitoring regime to ensure compliance and effectiveness.

Key takeaway: Effective water management in the UK requires careful planning, resource allocation, and continuous monitoring to ensure compliance with stringent environmental regulations.

Conclusion

Water management during construction is not a one-size-fits-all challenge; it requires a nuanced approach that considers the unique conditions of each site. By starting with robust modelling, understanding the limitations of traditional methods like SuDS during the construction phase, and being open to the use of chemical treatment, when necessary, we can ensure that our projects meet regulatory standards and protect the environment.

As a contractor, if your tender includes all of this, and your competitors don’t, then this should ring alarm bells with your client – in our experience it certainly does with the ones we advise. By embracing these regulatory backed strategies you’ll mitigate potential environmental risks and protect yours and your client’s reputation while setting a higher standard for environmental responsibility in the construction industry.

Take a moment to review your project’s water management plan. Are you fully prepared, or is there more you could do to protect your site and the environment?

We would like to express our gratitude to Jamie Ledingham of Highland Hydrology for his valuable support in preparing this article.